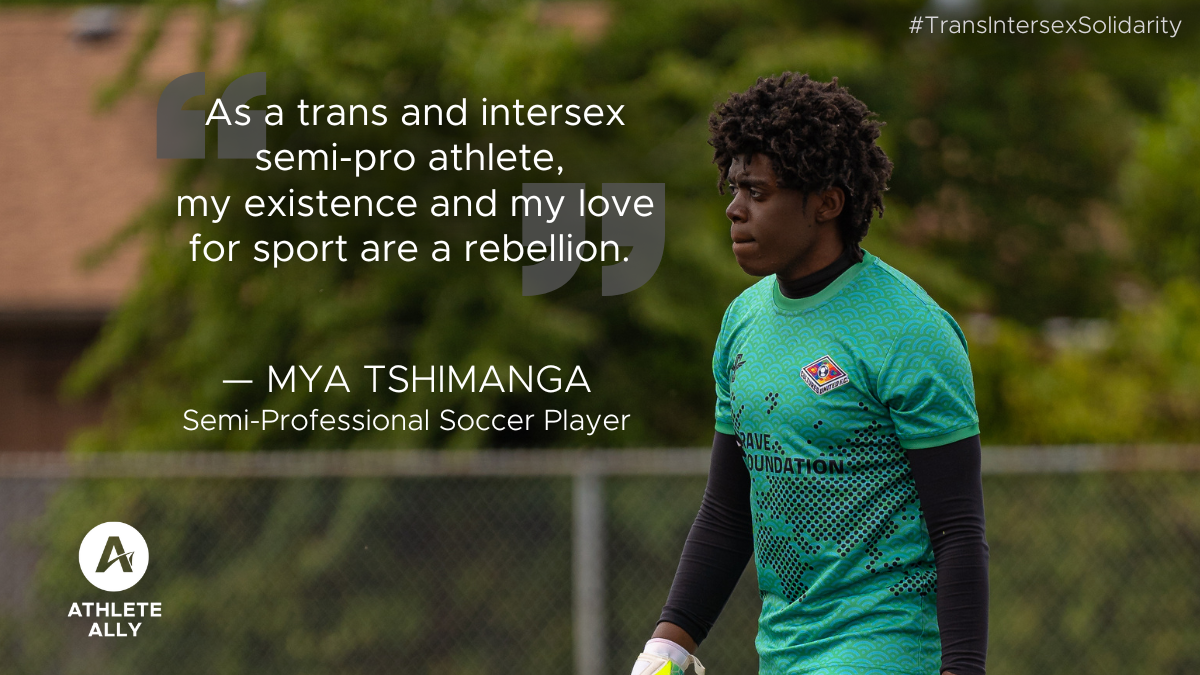

Semi-Pro Soccer Player Mya Tshimanga: Being a Trans and Intersex Athlete is a Rebellion

By: Mya Tshimanga, semi-professional soccer player

As a kid, did you wonder what your life would be like? I’ve always known I wanted to be an athlete. My name is Mya Tshimanga, and I’m a trans semi-pro soccer player aspiring to go professional in the next couple of years. The conversation around trans athletes today surrounds whether we have an “unfair advantage”— my life is living proof that we do not.

I’m no stranger to hardships and discrimination. I was born intersex and was forced to live my life as a boy growing up. When I was 19, I learned that I was intersex and that I never had a say in who I was, who Mya was. When I was 19, I came out as a woman. And when I was 19, I was forced into homelessness. I was homeless for about a year and a half, bouncing between sleeping outside in parking docks to homeless shelters to friends’ houses to transitional living centers. Society othered me because I was homeless, and homeless shelters othered me because I was trans. It wasn’t until I encountered a newer transitional living center called Dallas Hope Charities that I was able to get financially stable and get on hormone therapy, thanks to their then-CEO’s persistence and undying belief in me.

When I was 21, I saved enough money to move to Seattle and start fresh, away from my previous hardship. Eventually, I started gravitating back to playing sports. I started with playing pick-up soccer which was the first time that I realized my body is way different than it was in high school. Playing pick-up soccer against men felt like I was playing against a brick wall. When I was sprinting it looked like they were jogging. I had to give everything I had just to keep up with their physicality. Later that year, I decided that I needed more soccer in my life because my love for the game was starting to grow for the first time since high school. I joined an LGBTQ+ women+ team that had women and nonbinary players playing in a women’s league. That season was the first time I had that taste for competition and the drive to be the best player I can be. Playing with them was so liberating, and it was the first time I’ve felt like I belonged not just to a team but to a community. And I wanted more—I wanted to reach my potential as a player.

In spring 2022, I was checking my Facebook and I saw someone posting about their semi-pro club making their inaugural women’s team. I emailed the coach to tell them about my background as a player and as a person, explaining my transition and explaining how I’ve been following the NWSL policy on Hormone Replacement Therapy. He emailed back that he welcomed all players from all experiences and identities. I ended up making the team.

That season was a game-changer because I competed against incredibly fierce athletes. The players in semi-pro clubs were people that are currently playing in college (DI, DII, DIII, NAIA), or were players in high school who wanted to go pro. Some were even professionals from overseas who wanted to train during their off-seasons. Overall, the season wasn’t a good one for the whole team since we ended up being injury-ridden and were last of the league with not a single win under our belt. But individually, I felt like I was hitting the best I’ve ever felt as a player — I was averaging 11 saves a game.

But, I wanted more competition. I wanted to make playing football my career. So I found an agent that wanted to take me to some clubs in Turkey to trial me. But, my coach urged me to train and work on my weaknesses first, as he believed I could go pro.

I am living proof that these hateful narratives about trans athletes are false.

Mya Tshimanga

That summer, anti-trans sports bans started to appear out of nowhere. These bans were never about fairness in sports as they claimed to be. They were about pushing trans people out of sports and out of public life. These bans would reference my fellow trans athletes like Lia Thomas, creating false narratives of “unfair advantage” and failing to mention instances of trans athletes losing against cis athletes.

I am living proof that these hateful narratives about trans athletes are false. Legislators behind these bans cling to sexist rhetoric that trans women are taller and stronger than our cis counterparts, but I’m 5’10”, the average height of a women’s goalkeeper. Legislators cling to sexist rhetoric that trans women are stronger than our cis counterparts, but I’ve competed against cis athletes who are far stronger and fiercer than I am.

Playing sports has become a privilege for trans and intersex young people, when it should be a basic human right. I am privileged to play football in a time when many trans and intersex people are denied access to lifesaving benefits of sport. As a trans and intersex semi-pro athlete, my existence and my love for sport are a rebellion.